Moral Relativism on Trial in Ten Commandments Case

In light of our filing last week with the U.S. Supreme Court in ACLU v. DeWeese, some comments are in order on why this is both a unique and important case.

A little more than six years ago -- in fact, on the same day -- the Supreme Court handed down two decisions involving the public display of the Ten Commandments. In one decision, coming to the Court out of Texas, the display was constitutional and could stay. In the other, out of Kentucky, the display was unconstitutional and had to go.

How these apparently contradictory decisions are to be reconciled continues to be an issue for lawyers to litigate and law professors to debate.

The DeWeese case, however, is not just another Ten Commandments case. In Judge DeWeese's courtroom, the Decalogue is not displayed alongside other historical documents to show its role in the development of Western legal tradition. It is not displayed to symbolize the rule of law or that society needs law to function.

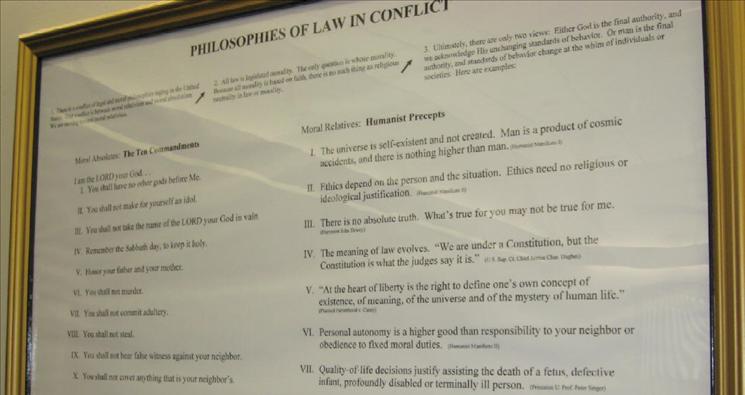

What makes this case unique is that in his poster, "Philosophies of Law in Conflict," Judge DeWeese uses the Ten Commandments to demonstrate the profound differences between a philosophy of moral absolutes and the ideology of moral relativism. It is a debate that goes back to the pages of Plato's Republic and it is one that continues to this day. And the ongoing argument over the nature of morality is more than an intellectual squabble. It is one that has immense implications for how we order ourselves personally and as a society. As the scholar Richard Weaver famously and succinctly put it, "ideas have consequences."

Judge DeWeese, who has presided over thousands of cases in his courtroom for 20 years, states in his poster that our communities are "paying a high cost in increased crime and other social ills for moving from moral absolutism to moral relativism...." One need only watch the nightly news to see the truth of what DeWeese writes.

Why, then, a lawsuit? Why did the ACLU sue Judge DeWeese over his poster?

DeWeese's display does more than point out the conflict between moral absolutes and moral relativism. He does more than point out the fact that a philosophy of moral relativism undermines society at its roots. Judge DeWeese writes in his poster that "I join the Founders in personally acknowledging the importance of Almighty God’s fixed moral standards for restoring the moral fabric of this nation."

That is what offends the ACLU. As far as the ACLU is concerned, any governmental acknowledgement of God, any governmental affirmation of morality grounded in a transcendental reality, is strictly forbidden under the Establishment Clause.

The ACLU's ongoing agenda to purge God from the public square needs to be stopped in its tracks. If the ACLU is right, then it is not only Judge DeWeese's poster that has to be tossed aside. So too must the Declaration of Independence and its proclamation that we receive our unalienable rights from our Creator; the Pledge of Allegiance and its affirmation that we are one nation under God; the national motto, placing our country's trust in God; the national day of prayer; even the invocation that begins public sessions of the Supreme Court, "God save the United States and this Honorable Court."

The ACLU, however, is wrong. The genius of America lies in the fact that we as a nation can affirm a belief in the Providence of God, without demanding that individual citizens do so; that our government can acknowledge religion without establishing one.

In fact, Judge DeWeese's poster states no more, and no less, than what George Washington said in his farewell address to the nation: "Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports."

The Supreme Court needs to set the record straight, not just for the ACLU, but for courts across the country, that a governmental affirmation that we receive our blessings and liberties from God does not violate the Establishment Clause.

If John Adams is correct, that "our Constitution was made for a moral and religious people . . . it is wholly inadequate for the government of any other," then the importance of this case, and the need for the Court to review it, cannot be questioned.